Extreme Learning Process 1.43

What is XLP?

XLP stands for Extreme Learning Process, a methodology that lets communities of learners design and conduct collaborative learning activities. Taking a look more closely at the name:

- Extreme: XLP explores frontiers, identifies boundaries, and helps participants push those boundaries.

- Learning: XLP enables individual learning, group learning, and large-scale crowd learning.

- Process: XLP has a explicit process, through which participants prepare, deploy, and execute missions.

We aim to become a crowd-learning system that facilitates collective learning in this increasingly complex world. Learners are empowered to work together within and between teams, and incorporate both digital and physical elements.

Due to advancing technology, educational institutions can now operate in ways unthinkable only a few years ago. This is because today it is possible to collect and process organizational behavior data in ways that were impossible before. Therefore XLP is not merely about improving individual learning, but also measuring and improving organizational learning.

XLP in a Nutshell

XLP is a compositional process with inputs, outputs, processes, and measurable effects:

A short introduction to XLP in Powerpoint format :A short introduction to XLP in Powerpoint format.

Inputs

- Sponsors and groups of participants, who become mission designers and mission executors. These participants come together for a specific learning objective and duration.

- Resources such as hackerspaces, campuses, mentoring, etc.

Activities

- Mission based learning, which is designed and executed by groups of participants. Each mission uses gamified techniques to impart valuable knowledge and skills with real-world applications.

- Digital publishing of all activities and results, in the form of containers of knowledge, via our Remix suite of tools.

Outputs

- Containers of knowledge, carrying a full record of participant activity, and able to be read, shared and deployed with ease

- Knowledge and skills transfer

- Credentials and qualifications, stored on the Blockchain. Access can be granted to selected employers and institutions to prove participants expertise.

- Crowd Learning, i.e. large scale collaboration on learning missions.

Effects

For participants:

- Real world decisions: XLP challenges participants to make financial, legal, cultural and technical decisions, so they can achieve goals set by the participant groups themselves.

- Real world experience: XLP is pragmatic. The XLP method induces realistic human dynamics, utilizes modern technologies, encourages participants to create social norms, and establishes executable regulations based on the design principles of the fast-evolving Internet.

- Tapping potential: XLP drives participants to realize their untapped potentials and emerging powers of collaboration through having them stretch the educational envelope by shifting the focus from teaching (top-down) to learning (bottom-up).

For educators and institutions:

- No-one left behind: XLP encourages an evolutionary process, which creates a digitally enabled learning context that delivers rich social-interactions and leaves no-one behind.

- Curating, not teaching: By placing participants in control of learning, XLP redefines educators' roles as curators of learning resources and as evaluators of participants' learning-potentials.

- Deeper, richer data: XLP provides network-enabled learning data management technology that enables stakeholders to record, analyze and identify learning trajectories to define new directions for progress.

A Short History of XLP

Since June 2012, XLP-based orientation programs and semester-long courses have been conducted at:

- Tsinghua University, Beijing

- National Taiwan University of Science and Technology

- Singapore University of Technology and Design

- Taylor's University, Malaysia

- Eurasia University, Xi'an

- Tianjin Vocational College of Mechanics and Electricity

Courses have also been conducted at many leading high schools in China. Due to XLP's experimental success, China's Ministry of Education has invited the founder of XLP to serve on the Design Committee of National Curriculum Standards on Technology Education, with the goal of rolling out XLP as a learning architecture and a learning activity design methodology for over 300 million registered students in the Chinese education system.

XLP is scalable and applicable to a broad range of students. A teacher from Tianjin Vocational College of Mechanics and Electricity stated his observation:

"In the past, I could only judge students' quality by their test scores. However, after seeing that students with low test scores can sometimes be the most productive contributors in XLP-enabled learning process, I realized XLP presents many opportunities for students to demonstrate their natural talents."

Mr. Wang Hong Yu, the General Manager of China's Open Course Resource Center, stated how XLP might affect his business:

"With shock and awe, I personally witnessed the transformative effect of a few XLP events on students. I realized that a radical transformation in education has already taken place here in China. The traditional textbook-oriented industry could no longer last. We have to re-position ourselves in the future ecology of education."

Why XLP? Why Now?

XLP did not spring fully formed from a vacuum. There is a specific context surrounding the framework and its development:

Computing Power

Roughly every 2 years, the number of transistors on a computer chip doubles[1]. The resulting increases in computational processing power strongly synergizes with skyrocketing levels of data storage and falling costs. This influences every aspect of our lives, and the opportunities to learn in new and different ways are expanding exponentially.

Big Data

Every second, gigabytes of data are being collected, and no one – or even any organization – will ever be able to access or process it all. However, learning communities can come together to deal with subsets of this data and solve real-world problems.

This big data makes what and how humans learn more important. As data collection and processing increasingly lets machines connect and aid human decisions (hence creating value), human ingenuity, creativity and intuition are becoming increasingly important. More and more, the only things that people should do are the things that only people can do – and this, of course, places a premium on humans' ability to learn.

Open Source

Open source gives anyone the right to use, change, or share a given technology, thus dramatically reducing the cost of using, copying, modifying, and redistributing software (and indeed, hardware). This means anyone can be a creator and build upon the achievements of those who came before.

Mobile Devices

Developments in mobile communications and the ubiquity of digital electronic devices mean that more people can connect to the internet – and each other – anytime, anywhere. This means newer, richer opportunities to learn from and with others, no matter where they are.

Containers and Clouds

Big data needs big computing power – too much for any one institution. With cloud providers like AliCloud or Amazon Web Services, anyone can run virtual machines to perform big computing tasks, and with the power of container platforms (Docker, Kubernetes) they can scale and replicate with ease.

Globalization

The problems of today's world require diverse communities to offer new insights. These problems are too big for just one individual or institution, but affordable Internet access is enabling people all over the world to collaborate in micro-learning communities to solve these problems. Learning and working together globally across boundaries of space and time – across all boundaries – is mankind's greatest hope for making progress, and XLP enables this crowd-learning and collaborative effort to improve the state of the world.

XLP pushes for the emergence of the world as we believe it should be – egalitarian and equitable, a world in which everyone has a fair chance to have their voice heard, and a fair opportunity to contribute to the progress of the world and humanity.

Summary

The above factors both enable and require new modes of learning which are increasingly collaborative, personalized, self-directed, active, engaging, and global. XLP has enabled communities of learners to form, disband, and learn collectively more easily and inexpensively than ever before. The ubiquitous interconnectedness of data, people, things, and processes, the opportunities for collaborative crowd-learning – and new modes of crowd-learning – will increase exponentially. These trends will enable learning to be measured in new ways, and will redefine what the outcomes of learning should be. XLP capitalizes on these trends and enables new learning environments and opportunities, while being enabled and indeed necessitated by them. What humans learn, and the way they learn, must and will be transformed.

How XLP Works

Missions

XLP's core activity is the mission. Participants either prepare the mission or execute it.

These missions engage individuals and the group as a whole. Each group designs and operates its own small (or "micro") learning community that serves the individual and collective aims of the creators and participants.

Each mission is governed by a Logic Model to deliver maximum learning value through hands-on activities. In this chapter we will give a high-level overview of the activities and participants in an XLP mission and the resources made available to achieve the mission goals. In the following chapters we will present detailed step-by-step breakdowns to help you prepare and run missions yourself.

Participants

XLP engages with learning communities of all shapes and sizes. They may be:

- Large or small

- Physically together, near each other, or spread around the world

- Of similar (or vastly different) ethnic, cultural, educational, professional, and religious backgrounds

- Similar (or different) skill sets, skill levels, interests, and life experiences

- Relatively homogeneous, or highly diverse

- Stay together for many years, or come together to design and conduct a single learning activity

These micro learning communities come together to learn something specific, often for a specific duration. Multiple communities can interact, and may later merge to form larger learning communities, just as amoebas divide and recombine in different ways. As a community becomes larger, it becomes more and more like the real world, and participating individuals, institutions, systems and societies can iterate upon increasingly optimal solutions.

Each community may have three kinds of members: Mission Designers (MD's), Mission Executors (ME's) and Sponsors. The Designers and Executors learn individually and collectively, and this community is a microcosm of a larger context – for example, a university, a society, or a nation. XLP challenges every learning team to be a focused, goal-oriented microscopic society in a digital publishing/learning workflow environment.

Mission Designer

Mission Designers (MD's) design and test learning missions in accordance with the goals of sponsors, tailored for participants based on the available resources and requirements.

MD's are generally divided into four or five groups that reflect Lawrence Lessig's Four Forces that are discussed in a later chapter:

- A law court and perhaps a patent office to regulate the legal interactions between ME's

- A media department to reflect the social norms of the ME's through social media, other digital media, and traditional media

- Market regulators to regulate the operation of the market

- Technology support to enable ME's to execute missions using the technology architecture required to do so

Mission Executor

Mission Executors (ME's) participate in the missions designed by Mission Designers, and later become Mission Designers themselves. While on the mission, they learn to execute at a higher level of complexity or speed, and learn how to guide others to perform the mission.

Sponsor

School/department that provides resources for XLP program.

Resources

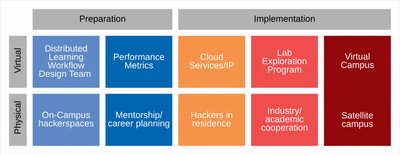

A learning environment encompasses resources in both the virtual and physical worlds. These can be further divided into two categories: Resources to prepare before the learning process and resources (which have been used and tested in the past) to implement during the learning process:

Outputs

Containers of Knowledge

Containers are the foundation of XLP. A container can be thought of as a box that contains software, the data needed to configure that software, and data created by users (i.e. digital assets). These containers can be installed and used anywhere, and data can be imported and exported easily.

- XLP creates replicable, learning missions in containers, which can then be installed and used anywhere in the world

- Our online platform, Remix, provides the infrastructure to perform this digitally

- Participants create digital assets in their containers using digital publishing, as a record and proof of the work they have performed in the mission.

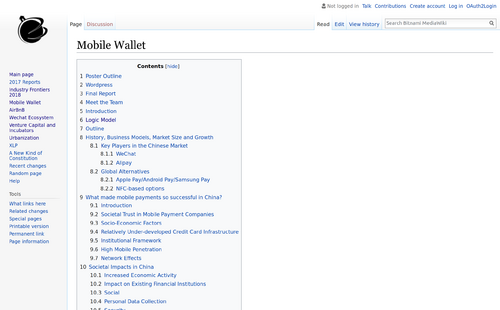

By taking part in the mission and digital publishing workflow, participants create a body of knowledge covering their area of study. This is in the form of a container which includes software (typically MediaWiki and other tools like WordPress), configuration, and content produced by the participants. These containers may contain many forms of digital asset:

Proposal or Report Form

Discusses the conclusion of a certain research study, or the conclusion of certain industry analysis ("research study," "business proposal," or "industry analysis report.")

Budget

Including both a planning schedule (i.e., a resource and human resource budget and timetable) in addition to a financial budget.

Short Movie

Usually a compilation of interesting video footage of the activity, annotated with written text and non-proprietary music.

Prototype Product

A book, pamphlet, brochure, or even physical product.

Example Containers

Team

One of the most important aspects and products of any XLP event is the friendship developed between participants. Ideally they can create a social network so they can always tap into these human resources for future cooperation.

Refined XLP Manual

Because everyone uses a similar mechanism to learn from each other, we can collect data on this to improve XLP as a general learning process – so that everything we do in XLP can be used as case studies or data to improve practices in future. The most direct contributions will be sections, refinements or revisions to the XLP operating manual that you are reading now.

XLP for Mission Designers

The job of a Mission Designer is to design the mission for Mission Executors, then deploy it and guide them through it. Typically a Mission Designer has been an active Mission Executor in the past.

Mission Designers put together:

- Constitution: Defines the goals of the mission, and rights and responsibilities of Mission Designers, Mission Executors, Sponsors

- Logic Model: Defines the context, goal, inputs, activities, outputs, effects, and external factors of the mission

- Mission Specification: Specifies the mission clearly

This process generally takes a month or so, since extensive planning is required.

It is highly recommended to "eat your own dogfood" while preparing the mission - namely using the XLP methodology itself (logic model, constitution, etc) to govern the mission design process, with the end goal of having students produce their own logic models, etc, as outputs of said mission. For that reason, MD's should become familiar with how executors execute XLP missions since designing an XLP mission is itself an XLP mission.

Kick-Off Meeting

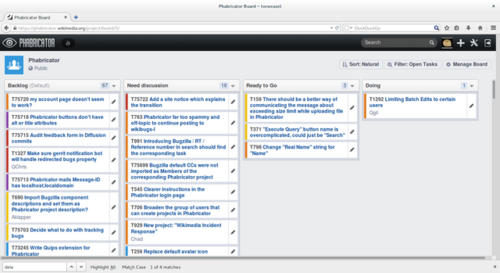

Sponsors, Mission Designers, and support stuff should come together to ensure mutual understanding of the XLP mission preparation process. Upon setting up the Digital Publishing Container, the team can use tools like Phabricator to assign tasks and deadlines.

Digital Publishing Container

Each learning community uses digital publishing tools (like MediaWiki) to publish their activities and results. These tools are contained in a Docker container which lets users access them online. MD's should coordinate with technical support staff to ensure these containers are deployed and fully tested, with a regular backup system in place.

Constitution

The constitution is a living document that lays out:

- Which entities can engage in an XLP mission

- The purpose of the mission

- Responsibilities of participants

- Rights of participants

- How to change or amend the constitution (typically via git or other version control systems)

Mission Designers write their own constitution which "overlays" the XLP Meta Constitution. Check an example constitution for reference.

This constitution is supplemented by a smart contract. Whereas the constitution provides the framework, the smart contract handles the specifics. The constitution is the overarching set of rules, obligations, privileges and rights for the membership of accounts, while the smart contract is one defined and created by the parties involved in a particular digital publishing workflow or creation. That is, every account is to be governed by both this overarching constitution, and a smart contract which defines the specifics of one's work in the XLP.

XLP for Mission Executors

Each Mission Executor goes through an extensive orientation program before engaging in the mission that the Mission Designers created.

Delegations, Groups, and Teams

Depending on the amount of people taking part in activities, they can be broken down as follows:

- A delegation may consist of several groups who attend a venue together, but work on different courses with frameworks different to XLP.

- A group is all the participants working on an XLP course together. They may (or may not) be part of a larger delegation.

- Each group is split into teams, each working on a specific project that they will be graded on.

Orientation Program

Usually involves digital identity, agreement reading/signing and quick overview of how to use digital publishing tools. Participants also gain experience dealing with many other people on the fly, encountering the courtroom, participating in market transactions, participating in media – i.e. learning how the four forces interact with XLP activities.

Digital Identity

Every entity in an XLP mission has a verifiable which they use to:

- Log in to the digital publishing tools stored in their container (like MediaWiki, WordPress, or NextCloud)

- Attach ownership to the content they generate

- Track their learning progress via built-in analytics tools

- Digitally sign the constitution and smart contracts

- Securely link their identity to their qualifications and credentials

These participating entities include individuals and organizations, as well as physical resources and technical services. Digital identities (like email addresses or OpenID) enable the tracking of every entity's contribution to the crowd-learning process, and allow participants to sign Smart Contracts.

Constitution Reading

Before each XLP mission, each prospective participant reads through the constitution to learn the mission framework. This details the rights and responsibilities of each participant in the activity, in addition to services provided by the sponsor. Participants digitally sign a Smart Contract (stored on the Blockchain) stating that they understand the details of the constitution and their responsibilities, and an agreement stating that they agree to abide by the overarching constitutional framework during the activity.

Lab/Knowledge Exploration

"Taster" classes allow participants to visit many laboratories and researchers in a big campus (e.g. Tsinghua University's laboratory exploration program that makes available more than 100 laboratories and gets participants on campus to see each other's research results.) This gives a broader context of available technology and research results.

Some examples include:

- The Intelligent Manufacturing Incubator at Zhongguancun

- The Digital Capability Center at iCenter, Tsinghua University

- Other local high tech companies

- Tianhe Super Computing Center

- Tianjin High Tech Zone

The Mission

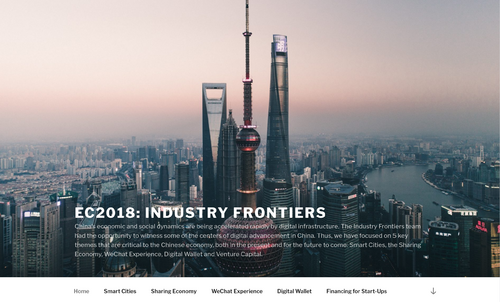

Mission Executors will form teams and create a digital publication, for example an Industry Analysis Report (IAR), based on field trips, in-person interviews, and lectures conducted by speakers and tutors. Ideally, Mission Executors should collect and compile relevant industry indication data, pictures, and videos taken on field trips or daily observations during the program, and integrate them into their publication.

All teams will collaborate on a hosted wiki to write and collate their reports, and then present the finished products on a visually appealing blog and as a class presentation.

Missions usually fall into one of three tracks, each of which use different tools to create different outputs:

- Industrial frontier: Participants globally search and compile relevant information, and creatively tell a compelling story using trustworthy data sources and presentation techniques.

- Computational thinking: Participants apply optimization technologies and understand the principles of optimal limits, and can thus apply optimization to all their learning activities.

- Domain Specific: Participants learn domain-specific vocabulary and rules, so that they can leverage existing bodies of knowledge in an organized manner.

Typically, a mission follows five steps:

Mission Breakdown

Decomposition and Recomposition

Each XLP Mission follows our V Curve:

Starting from the left of the diagram, participants break down (decompose) the mission until they get to the most basic (atomic) level, and then rebuild (recompose) the constituent parts into potential viable outputs. Breaking it down step-by-step:

- Mission specification.

- Decomposition of mission specification.

- Decompose and repeat steps 1-3 until you reach the atomic level. Keep going down, machine checking if you have met the specification. Must be at the atomic level.

- Go back up once you have defined the most basic decomposition.

- Propose a solution of some sort. You can use machines to generate new solutions. Frequently test to see if it matches your specification.

- Pick the best option and digitally publish it.

A useful analogy is a Lego set:

- The mission specification would be the picture of the finished model on the box

- The mission would be to build the model

- The most atomic level is the individual Lego bricks

Participants would look at the picture on the box, decompose it into component parts until they reach the brick level, then work out the best way to recompose it (or potentially build something even better) from there.

Logic Model

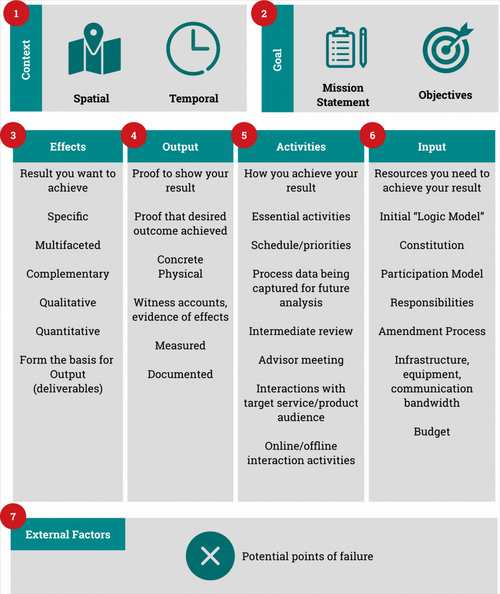

A logic model (also known as a logical framework, theory of change, or program matrix) is a tool used by funders, managers, and evaluators of programs to evaluate the effectiveness of a program. They can also be used during planning and implementation. Logic models are usually a graphical depiction of the logical relationships between the resources, activities, outputs and outcomes of a program. While there are many ways in which logic models can be presented, the underlying purpose of constructing a logic model is to assess the "if-then" (causal) relationships between the elements of the program.

As part of their digital publication, teams create a one-page logic model, taking into account activity context, inputs, activities, effects, external factors, and outcomes.

Each of the boxes below will have precise linguistic properties that can be examined by human or machine (via Natural Language Processing), to know if the information in the box fits the specified requirements. In this way, participants can be assessed and certified automatically, using Blockchain-witnessed process data collected using the Remix platform.

1. Context

- What's your current situation or context?

- Includes spatial and temporal description (where will you do the activity, and when?)

2. Goal

- What do you want to do?

- Imperative statement, for example "conquer Rome," or "land a man on the Moon"

3. Measurable Effects

- How will you determine success?

- Set of conditional statements. Output will be measured against these to confirm it has achieved desired goal

4. Output

- What will you deliver?

- Concrete objects like micro-movies, logic model documents, industry analysis reports, financial statements, etc

5. Activities

- What do you need to do to succeed?

- Set of partially ordered activities, outlining what happens during the project and how to accomplish the project goal

6. Input

- Resources required to execute the mission, including budget, human skills, head counts, etc

7. External Factors

- What factors that could prevent the team from achieving their goal?

The logic model is one of the first activities each team conducts, which helps to build a common understanding of the mission as well as the influencing parameters. During the next steps, continuously referring back to the logic model helps them check that they are consciously aware of their own actions.

Using the logic model ensures that every task or project starts with explicitly-analyzed test cases, originating from Test Driven Design. Each step of the model feeds into the next step, generally with a one-to-one relationship. Similar to writing a computer program, the logic model has two stages of checking/analysis:

- Static Analysis: A way to read the model itself, and see if the content in all boxes is consistent and relevant.

- Dynamic Analysis: A way to use the "measurable effects" to confirm output matches expected outcomes, and if task performance fits the goal.

Many examples of logic models can be seen from the teams that took part in Experience China 2018.

Mission Statement

A mission statement acts as a carrier of culture, ethos and ideology[2]. Many mission statements are pithy and up-beat, and deal with abstractions possessing 'a strategic level of generality and ambiguity'[3]

A team's mission statement should capture the essence of their goals and reflect their specific niche. The best mission statements are clear, concise, and useful (informs. focuses. guides.)[4]

Examples

- Public Broadcasting System (PBS): To create content that educates, informs and inspires.

- charity: water: Bringing clean, safe drinking water to people in developing countries.

- National Parks Conservation Association: To protect and enhance America’s National Park System for present and future generations.

- TED: Spreading Ideas.

- Defenders of Wildlife: The protection of all native animals and plants in their natural communities.

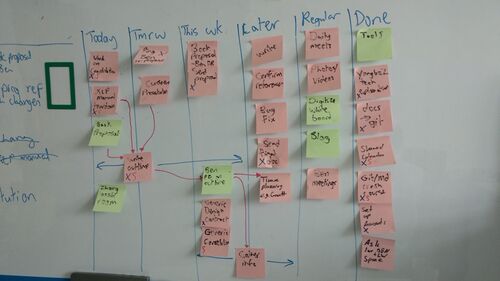

Planning and Management

Mission Executors use physical resources like whiteboards, post-its and note paper, and digital resources like Phabricator to storyboard their mission, assign tasks, and set a schedule.

Scheduling and Task Allocation

Ideally use a whiteboard board, with post-it notes:

- Each team member writes down a list of tasks they think need to be done

- Team comes together to share their post-its, and come to consensus

- Connect post-its with whiteboard markers to mark related ideas

- Post-its are put on kanban, arranged by schedule (today/tomorrow/this week/later/done)

- Each activity is assigned to a team member and recorded on Phabricator

Story-boarding

Teams designing a product or producing a video may find it useful to produce a storyboard, to visually organize their story or use case.[5]

Briefings and Debriefings

At the beginning of each day, the team coordinator should meet with the team and ensure everyone is up-to-date and clear on their tasks. Some example questions include:

- What thoughts have you had on the project since the end of the last working day?

- What tasks will you be working on today?

- What obstacles do you think may pop up? (and as a team, work out how to overcome them)

- What other commitments do you have today?

At the end of the day, we suggest a debrief to ensure the team achieved everything they planned. Some example questions are:

- What did you get done today?

- What did you plan to do, but didn't do? Why not?

- What surprises (good or bad) came up? (and as a team, work out how to overcome those bad surprises if they happen again)

- What's your plan for tomorrow?

- Any other business?

Activity Coordination

Based on the planning done in the previous steps, each team collects data via interviews with industry experts, site visits, online and offline research, and surveys. All research must be cited and collected on the wiki.

Surveys

- Writing good survey questions

Research

Some helpful links include:

Product Development

Note: Not all XLP courses require a product development step, for example when writing Industry Reports, this step would likely not be required.

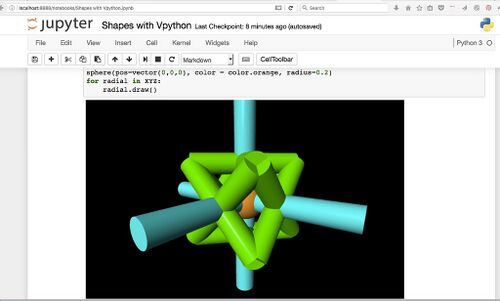

Mission Executors use tools like Jenkins, Modelica, Jupyter Notebook, and other prototyping and integration tools to develop their product, which may be software, hardware, or a business idea.

Digital Publishing

Many of the mission objectives you will be graded on revolve around digital publishing. Each group participating in the course will have their own digital container that holds the software and data you will use and/or create during the course.

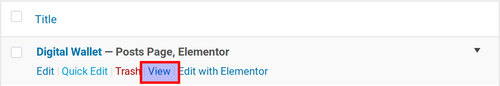

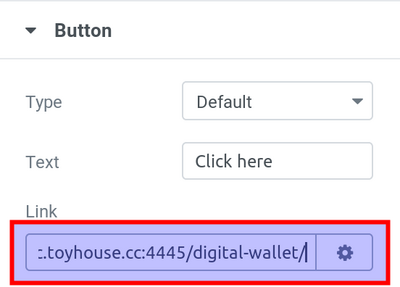

When you sign up for the course, you should be given a URL for your container and a unique login and password. If you haven't, please speak to your coordinator. The software you will use is WordPress and MediaWiki

Wiki

Mission Executors use the wiki to group edit your report and other documents.

A wiki is a website on which users collaboratively modify content and structure directly from the web browser. In a typical wiki, text is written using a simplified markup language.

Wikipedia is by far the most popular wiki-based website, and is one of the most widely viewed sites of any kind in the world, having been ranked in the top ten since 2007. There are tens of thousands of other wikis in use, both public and private, including wikis functioning as knowledge management resources, notetaking tools, community websites, and intranets. The English-language Wikipedia has the largest collection of articles; as of September 2016, it had over five million articles.

We use Mediawiki, the same software that runs Wikipedia, to allow participants to collaboratively create reports and other documents.

A guide to using MediaWiki is in the appendix.

Blog

After your report is ready, you will use the blog to create pages and present it in a visually appealing manner.

A blog (short for "weblog") is a discussion or informational website consisting of posts (diary-style updates, displayed newest-first) and pages (more permanent information).[7]

Our blogging software is WordPress: a free and open-source content management system. It is most associated with blogging, but supports other types of web content including more traditional mailing lists and forums, media galleries, and online stores. Used by more than 60 million websites, including 30.6% of the top 10 million websites as of April 2018, WordPress is the most popular website management system in the world.[8]. Our WordPress installation includes several plugins to make editing easier, most notably Elementor.

A guide to using WordPress and Elementor is in the appendix.

Presentation

Each team will create a presentation to present the work they've done, and present to the class. Typically, a presentation should last 5-7 minutes, plus questions and answers afterwards. Don't worry about getting everyone on stage to present - instead limit it to 2-3 speakers.

Since Microsoft PowerPoint is the industry standard (and you may not be presenting from your own computer), we recommend creating your presentation in pptx format. Don't use Google Docs or other online office suites, since connnectivity (due to VPN or lack of network) may be an issue.

After each team has presented, everyone will regroup and the group will nominate a team to create one final presentation to summarise the industry reports of all the teams.

Poster

Quite often, all of the teams will come together as a group and create one or more posters that present the work they've done. While other groups may use markers or a collage to create their poster, we recommend sticking with the theme of digital publishing and creating it with software like Adobe Illustrator.

Example poster from Experience China 2018: Industry Frontiers:

Useful Resources

We encourage participants to use Creative Commons (CC) licensed materials in their work. Creative Commons licenses let others copy, distribute, edit, remix, and build upon various works, all within the boundaries of copyright law.[9]

The following websites let you search for content licensed under Creative Commons. Don't forget to cite your sources and respect the license when you use these materials!

- Creative Commons Search - images, music, video

- Noun Project - symbolic icons (for example, world, people, internet, etc)

- 14 Websites To Find Free Creative Commons Music

- The Five Best Places To Find Free Creative Commons Photos

- 5 More Places to Help You Find Quality Creative Commons Images

Evaluation and Assessment

Using secure technologies like the Blockchain, XLP tracks learner activity at different levels, assessing how individuals contribute to their group and how a small group contributes in turn to larger communities. This allows individuals and teams to receive personalized feedback and improve over time. This in turn applies to grading and certification, with both micro-credentials and full degrees stored on the Blockchain. Access rights can be granted to other universities or employers to show tamper-proof evidence of achievement.

Remix: The XLP Online Platform

Think of the world you live in: Imagine the classroom of the future:

In a world that is becoming increasingly digital, it is essential to teach the skills required to navigate through the digital environment as early as possible. A gap is opening between those who are technologically literate and others who are yet to be comfortable with handling software. The ones who are on the wrong side of this gap will eventually suffer detrimental implications to their careers and lives. Such individuals will not be able to take part in collaborative work, thereby limiting their ability to increase their knowledge. Already, individuals and institutions lack the tools to create new digital assets or work with the existing digital information, both of which decrease their overall potential. Clearly, students need a solution to escape this situation. Imagine a classroom of the future that is modeled after the reality outside the classroom. If the reality outside the classroom is one pervaded by digital tools, so should the classroom. Remix makes sure this happens. Students will no longer study for exams but prepare for the challenges that await them in the future. It helps them work and self-manage teams with tools like Phabricator and Git, while allowing teachers to track student progress and individual contributions (captured using a digital data processing system) towards their respective projects using GitLab. Without such digital tools, organizational consciousness can't be brought to human attention and organizational learning can't happen.

Trustworthy computing technologies such as Blockchain technology are integrated into Remix. These ensure immutability while ensuring credit is given where credit is due.

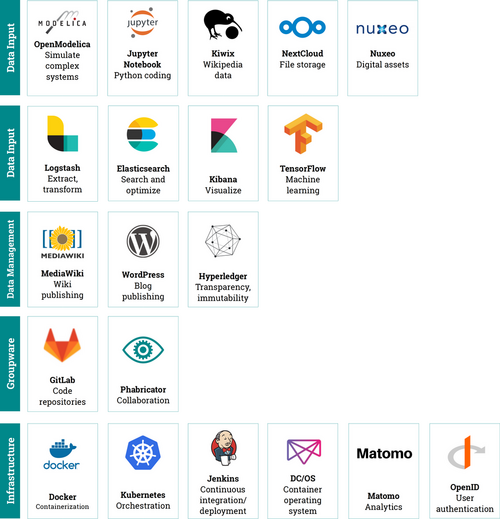

Remix Tools

The Remix platform offers a large array of powerful tools, manageable by anyone and scalable to any size.

These tools will be an important asset for any modern educational institution for which it can fully develop the intellectual potential of its students and staff. The platform democratizes services that were previously limited to such an extent that only established companies were able to utilize their full potential. These services are now combined into a single platform allowing any individual or institution to start their digital transformation. Without the need for continuous online connectivity, the platform can be brought to the farthest corners of the globe, where a new generation of individuals can start fulfilling their computational needs. In short, Remix can bring the tools used by established software companies into any classroom or home enabling anyone to take part in the future of the digital world.

Together, participants can create new data using tools like Jupyter and OpenModelica, or analyze and optimize existing information using Elasticsearch and TensorFlow. Ultimately, every individual can create or take part in a Digital Publishing Workflow – a cycle going from Data Input to Data Management to Data Publishing, all from their own laptop in one single application. This is Remix.

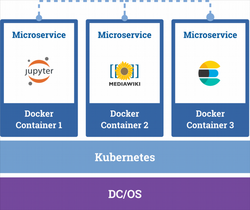

What is a Microservice?

The central idea behind microservices is that some types of applications become easier to build and maintain when they are broken down into smaller, composable pieces which work together. Each component is continuously developed and separately maintained, and the application is then simply the sum of its constituent components. This is in contrast to a traditional, "monolithic" application which is all developed all in one piece.

Applications built as a set of modular components are easier to understand, easier to test, and most importantly easier to maintain over the life of the application. It enables organizations to achieve much higher agility and be able to vastly improve the time it takes to get working improvements to production. This approach has proven to be superior, especially for large enterprise applications which are developed by teams of geographically and culturally diverse developers.[10]

Remix Microservice Overview

Data Input

Data Input describes the different ways through which data may enter the Remix platform. In the Digital Publishing Workflow, Data Input lies between Data Publishing and Data Management, as previously published data can act as input for Data Management.

Generally, data may enter the system from three source types or combinations of them.

Data Creation

Remix comes with microservices from which new data can be created. For instance, OpenModelica enables users to create simulations of complex systems. The data produced by these simulations can then be saved for later use. Another service, Jupyter, allows for coding, solving equations, and showing their visualizations that can then be shared in real time among different users. Again, all the data created can be saved for later use.

Online Data

Remix also allows users to source data from the internet such as databases, wikis, or pictures. Again, different microservices are available and integrated for this purpose. Data may be accessed directly from the internet or downloaded first (for instance, to be brought to regions where internet access is spare or Internet is slow). Kiwix, for instance, offers the entire Wikipedia, WikiVoyage, TED Talks, and more for free to download on their website. This data may also be used as input for Data Creation, subsequently representing a combination of data.

Private Data

Remix enables users to use their own private data as input for Data Management and Publishing. For this purpose, the platform comes with microservices such as Nuxeo, which is a digital asset library already used by institutions, companies, and individuals to manage their digital assets and NextCloud for file storage in the cloud. Hence, they can tap into their existing data and use it as input for other microservices to create new data, again representing a combination. Generally, such private data may belong to an individual, an institution, or a company who can scale up their data storage as required without having to scale the other microservices thanks to the underlying system architecture.

Data Management

The data management part of Remix utilizes four different tools to perform a number of tasks. In the Digital Publishing Workflow, Data Management lies between Data Input and Data Publishing. The purpose of data management is to load the given information from the different data inputs, then optimize it so that it becomes searchable and produces the best results, which in turn can be visually presented to the user. This is possible through the use of the ELK stack from Elastic, consisting of Logstash, Elasticsearch, and Kibana, in combination with the machine learning capabilities of TensorFlow. These tools are combined to allow users to perform queries on wide array of data that in turn, can be optimized based on an infinite number of characteristics. The following section will describe each tool and how they are an integral part of the of the Remix framework.

Logstash: Data extraction, transformation, and loading

Remix consists of a large number of data sources that each produce a large quantity of data, in many different formats. It is therefore necessary to have a tool that can extract, transform and load the input data into the next step of the process. This is where Logstash is used. Logstash is an open source server-side data processing pipeline based on the extract, transform, load (ETL) process.

Each step has varying degrees of complexity, that will be explained in the following sections:

The first job carried out by Logstash is the extraction of data from the different defined sources. Extraction is conceptually the simplest task of the whole process but also the most important. Theoretically, data from multiple source systems will be collected and piped into the system for it later to be transformed and eventually loaded into the system. Practically however, extraction can easily become the most complex part of the process. The process needs to take data from the different sources, each with their own data organization format and ensure that the extraction happens correctly so that the data remains uncorrupted. This is where validation is used. The extraction process uses validation to confirm whether the data that was extracted has the correct values, in terms of what was expected. It works by setting up a certain set of rules and patterns from which all data can be validated. The provided data must pass the Transform Load validation steps to ensure that the subsequent steps only receive proper manageable data. If the validation step fails, then the data is either fully rejected or passed back to the source system for further analysis to identify improper records, if they exist.

The data that is extracted then moves on to the data transformation stage. The purpose of this stage is to prepare all submitted data for loading into the end target. This is done by applying a series of rules or functions to ensure that all business and technical needs are met. Logstash does this by applying up to 40 different filters to all submitted data. When filtering is completed, the information is transformed into a common format for easier, accelerated analysis. At the same time, Logstash identifies named fields to build structure from previously unstructured data. In the end of the transformation process, all data in the system will be structured and in a common format that is easily accepted by subsequent processes.

The last part of the ETL process is the load phase. The load phase takes the submitted and transformed data and loads it into the end target. There are certain requirements defined by the system that must be upheld. This pertains to the frequency of updating extracted data and which existing information should be overwritten at any given point. Logstash allows the system to load onto a number of systems, Remix does however only require that Elasticsearch receives the data.

Elasticsearch: Search and Optimize

Search and optimize are two key attributes of any data management system. It allows a system to filter away all the unwanted data and prioritize the results based on a number of given attributes. Search and optimize are not functions that are limited to basic keyword searches, but can instead be used for a wide variety of possibilities. Everything from choosing the correct strategy in a game of chess to simulating the trajectory of a moving vehicle. In all these cases, the function utilizes the available information from the different data sources in combination with machine learning intelligence to give the desired outcome To achieve this Remix uses Elasticsearch and TensorFlow. Elasticsearch is a distributed, RESTful search and analytics engine that stores data in a searchable manner. All the data that is passed through Logstash eventually ends up in Elasticsearch. Here it is structured and analyzed to allow users to search based on their chosen parameters. The given parameters are in turn used to filter away all the unwanted results. What remains is a list of results that in one way or another are linked to the original search criteria. This list is, in turn, handed to TensorFlow.

TensorFlow is a mathematical library using deep neural networks in order to analyze data. The system takes in the data that was selected by Elasticsearch and prioritizes/orders it according to the pre-determined criteria. This gives the user a selected number of results that should be suited exactly to their defined needs.

When it comes to searching and optimizing, Remix's key difference compared to other services is that results are purely based on the user. If a user specifies a certain interest or academic field that they are studying, then the optimization will be created with that parameter as a focus point. Thus, opening up focused research where all advertising-based rankings or unwanted results are removed.

Kibana: Data Visualization

In certain scenarios, the outcome of the data management process doesn't come in the form of links or lines of text. In these cases, it is often required that the data goes through some sort of visualization in order to turn it into something that is manageable.

This is carried out by Kibana, the last tool in the data management process. Kibana is a data visualization plugin that works with Elasticsearch to provide visualization on top of the content that has been indexed. It takes all the data that the user has asked for and gives a visualization if it is applicable. Kibana can therefore also be seen as being part of the data creation aspect of Remix.

Data Publishing

The final aspect of any standard research project concerns the publishing of results and conclusions.

For this reason, the final part of the Remix framework is data publishing. The purpose of this step is to ensure distribution of new data to a wide audience while guaranteeing rightful credit and ownership of published research and findings. To do this, the platform uses two main tools, MediaWiki and Hyperledger, in combination with the machine learning capabilities of TensorFlow.

MediaWiki is a digital publishing tool created by the Wikimedia Foundation. It allows information to be published in a structured and navigation-friendly way. Remix uses MediaWiki to allow institutions or individuals to create closed or open wiki spaces in which all their information and research can be published. Each publisher then creates a distinct name for each new published article or piece of information. All the information on the given wiki space is then individually connected using the deep neural network capabilities of TensorFlow, as mentioned in the previous chapter. TensorFlow analyses each piece of information and carefully links it together with other related information. This, in the end, produces a wiki space which is full of research articles and other information, in combination with existing Wikipedia data, that is fully connected. Furthermore, connections and recommendations of articles can be made based on user preferences. In other words, if a user is studying biology and is doing research on the flight patterns of butterflies, then Remix will start creating more links and finding more research articles on that topic specifically. In that scenario, it might connect the flight patterns of butterflies to the evolution of airplane wing structures.6

Ultimately, a person can, through Remix, have access to a deeply interconnected network of research, published articles, and existing data from the internet.

To ensure all information in the system is untampered with and that publishers are rightfully credited, Remix uses trustworthy computing technologies such as Hyperledger. Hyperledger is an open-source collaborative blockchain technology that ensures transparency and immutability of all data in the system. This, in turn, ensures that any information for which there may be a rightful owner is credited as such. These tools open up a new dimension of the digital publishing process that allows institutions and individuals to contribute their knowledge to a greater audience.

Groupware

Remix provides Phabricator and GitLab as a platform for participants to collaborate. GitLab is an open-source web-based Git-repository manager with wiki and issue-tracking features, allowing users to upload and share code and digital assets, while ensuring no conflicts occur between versions.

Phabricator is is a suite of web-based software development collaboration tools, including a code reviewer, repository browser, change monitoring tool, bug tracker and wiki. Phabricator integrates with Git, Mercurial, and Subversion. Participants can use it for project management and coordination within (and among) teams.

Architecture

The interconnectedness of services in Remix is made possible using the Docker platform. Docker uses container technologies to allow microservices and other digital assets can be run in easily-replicable sandboxes and not interfere with each other. Unlike virtual machines, containers do not require a guest operating system which makes them more lightweight, allowing for more or bigger applications running on a server or single computer.

With Docker container technologies, we can re-define all digital assets into three main categories: content data, software data, and configuration data. These categories can be tagged using a hash code (similar to Git or Blockchain labels) and can be traded by swapping out "tokens" or hash IDs of the asset. This allows participants to easily install different software services and start using the asset almost instantly. The end result is that participants and instructors can better manage learning activities, and use one consistent namespace to organize all their assets.

Hence, a multitude of containers can easily be combined in a single application. This can be done through Docker Compose. While Docker focuses on individual containers, Docker Compose engenders scripting the installation of multiple containers that work together to create a bigger application. Microservices in Remix talk to each other to modify and move data from its creation, to its management, and publishing. At the same time, since the microservices are still housed in their respective containers, any service may be added or removed at any time without damaging other containers.

Remix also enables deployment, monitoring, and scaling microservices with Kubernetes, a tool specifically designed for this task. Microservices can then be scaled individually and independently from each other (thanks to their containerization), specific to the needs of the user. Matomo (formerly known as Piwik) is an open-source analytics software package (similar to Google Analytics) for tracking online visitors, analyzing important information, and track key performance indicators. Remix uses this software to track usage of the platform by participants.

Finally, Mesosphere DC/OS acts as the foundation of the system and adds a layer of abstraction between Kubernetes and Docker and the user's underlying OS. This operating system for datacenters works specifically well with microservices and takes care of resource allocation and makes the system fault-tolerant.

In summary, Remix is an platform that is lightweight, modular, and easy to install, use, and scale, enabling everyone to make use of the powerful microservices included. The platform achieves this using a three-part structure with the microservices being the highest layer of abstraction followed by the combination of Kubernetes and Docker and completed by the Mesosphere DC/OS.

Education on the Blockchain

The blockchain is a decentralized technology that acts as a digital ledger for recording transactions between different entities, both human and machine. Originally devised for the digital currency Bitcoin, the blockchain is now being used for many other purposes, including in education. Below is our guide to making education fairer, deeper, and more accessible to all by using the blockchain.

“The blockchain is an incorruptible digital ledger of economic transactions that can be programmed to record not just financial transactions but virtually everything of value.” - Don & Alex Tapscott, authors Blockchain Revolution (2016)

Historical Context

Like many phenomena, over time education has moved from a centralized cathedral model to a more decentralized bazaar model[11]:

Education 1.0: Traditional Education

Traditional education consists of physical university campuses, and students attending classes on-site. Students do coursework, lab work, theses and exams, and these are graded by professors, usually at the end of the semester. In education 1.0, students are generally passive consumers of education, receiving information from academic staff[12]:

Because traditional education is based around a physical space and a limited number of professors, students are limited by number and location, and financial and academic requirements for entry can be very high[13] [14].

Because assessment is done by humans, fraud and bias can creep in from both students and faculty. Indeed, A large-scale study in Germany found that 75% of the university students admitted that they conducted at least one of seven types of academic misconduct (such as plagiarism or falsifying data) within the previous six months.[15] Some examples of dishonest behavior include:

- A woman using an impostor to take a college English test[16]

- A Japanese medical university manipulating entrance exam scores to limit the number of women admitted[17]

- Thousands of UK nationals buying fake degrees from “diploma mill” in Pakistan[18]

- 50,000 UK university students were caught cheating in the previous three years, amounting to a so-called “plagiarism epidemic”[19]

Summary

In Education 1.0:

- A student browses universities within physical proximity and signs up for a course, typically for several years

- The student physically goes to classroom and sits in front of professor

- The student writes thesis and sits exam

- The professor grades the thesis and exam

- The professor awards a grade to the student

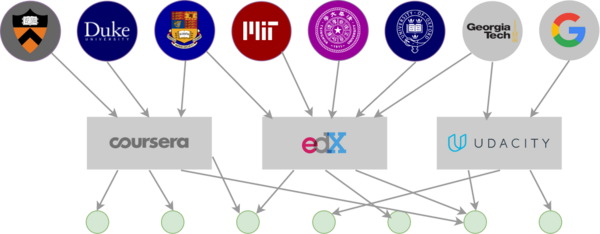

Education 2.0: MOOCs

Education 2.0 moved education online, with Massive Open Online Courses, offered by sites such as Coursera, Udacity, and EdX. These courses are open to anyone around the world, and students are given regular feedback on their performance via the system.

Education 2.0 is the age of networked monoliths. Whereas previously universities offered courses only to their own students, now they offer courses on MOOC platforms too. However, these MOOC platforms are themselves centralized monoliths. Students may take courses on one more MOOC platforms.

Typically students sign up for a MOOC with their existing digital credentials like a Facebook login or email address. While convenient, these are not solid proof of identity in the way that a secure digital identity (like public/private key) would be. At best, some services offer biometric identity via webcam.[20]

Interaction between students (if there is any at all, which is not often[21]) is via the MOOC’s forum, and is typically centred around problem-solving and support, rather than content creation, project-based learning and digital publishing. After the course is finished students disband (again, if they ever banded together) and go their separate ways. This limits the possibility for collaboration and groupwork.

Courses are typically assessed by algorithm [citation needed], from students answering multi-choice questions or writing a program that generates a specific output. This limits many MOOCs in terms of flexibility and creativity.

Summary

In Education 2.0:

- Student signs up for a course on Coursera, EdX or another platform offering educational courses, typically for a few weeks or months

- Student works from wherever they are in the world

- Student coursework is graded by the MOOC system and assessors working for the MOOC

- MOOC system awards grade to student

But how do we ensure the student is actually the one doing the work?

Physically decentralized but central MOOC system

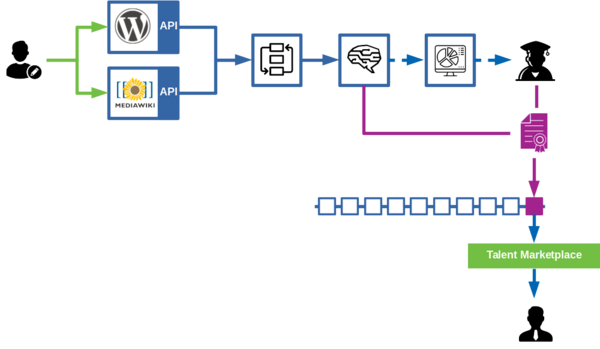

The Future: Education 3.0: Education on the Chain

With Education 3.0 we can modularize, granularize, democratize and decentralize education further:

- The line between educator and student gets blurred, as anyone can directly offer courses or tutoring and get paid for it

- Students can learn from anywhere in the world, from a single lesson to a series of courses

- Students and educators can share the materials they create, instead of them languishing on a hard disk

- Educators can spend less time grading and more time doing valuable tasks

- Qualifications can be verified and trusted

We do this by leveraging the power of the blockchain, specifically Ethereum.

Ethereum is a blockchain that enables anyone to create decentralized applications and smart contracts.[22] A smart contract is a legal contract in the form a computer program stored that enables secure, verified transactions between two or more entities.[23] This program is encoded on the Ethereum blockchain, and typically takes cryptocurrency as input. Parties sign the contract using their digital identity, typically in the form of a PGP private/public key pair.

Choosing a Course

The blockchain allows us to decentralize the MOOC concept further and allows decentralized marketplaces for courses, enabling content creators to offer their own curriculum, and giving users confidence with a built-in rating system. Students from anywhere in the world can browse this marketplace and elect to take a course by signing a smart contract.

Since anyone can be a course provider in education 3.0, the line between educators and students blurs considerably. Anyone can offer their materials and assistance (via one-on-one or one-to-many personalized tuition) on this platform. Participants browse the offerings, and find the course that best suits them. They can take the whole course, just certain units, or specific guidance from the course creator.

Because there is less human effort required in assessments, smaller machine-graded courses can easily be offered. These “micro-qualifications” cover specific niche skills or disciplines, for example the React Javascript framework.[24]

Course Signup

During course signup, students read through the course #constitution, which outlines their rights and responsibilities. This is both a human-readable document and embodied digitally in the form of a smart contract. Students sign this smart contract with their digital identity to show they have read their rights and responsibilities during the course.

Coursework

Depending on the type of course, different types of coursework may be done:

Individual Learning

May consist of watching videos, answering multi-choice questions, and writing code that creates a specific output. Similar to many programming courses in MOOCs. Students can offer support to each other via the platform’s forum and social features.

Group Learning

More project-based. Students do coursework on digital publishing platforms like MediaWiki and WordPress, which they sign into using their digital identity, ensuring any data they create is tied to them. These services have open APIs, so their data can be extracted and stored on a blockchain (either private or the main chain) to ensure data integrity.[25]

Crowd Learning

Any student can create a portfolio on a global student expertise exchange platform (similar in concept to Upwork) and seek out other students around the world who need their skills. This creates a marketplace for students to share knowledge and expertise, and enables large-scale crowd learning.

Many students can cooperate to create a single digital asset, on which they will be jointly assessed, and they can then share this asset (or subsections of it) on a decentralized digital asset sharing platform.

Assessment

For assessment, student-created data is gathered and stored on the blockchain to prevent tampering. It is then sorted using tools like the Elastic Stack, then processed, checked for plagiarism, and assessed by machine learning (with tools like TensorFlow). It can then be aggregated, ranked, and visualized for professors to perform their own assessments if required.

Grading and Qualification

As part of the assessment, a student’s qualification will be signed by the institution (for example, Tsinghua University) and stored securely on the main blockchain, allowing access by employers, institutions and anyone else to whom the student grants access via app or other means.

By tying every step of the course to a student’s verifiable digital identity and assessing by machine instead of humans, we greatly reduce fraud, bias, and human error in the system, and can scale education to deal with thousands of learners. Qualifications can be verified and trusted by students, universities, and employers.

Access to these qualifications can be encoded as a QR code which could be embedded in a badge via the OpenBadge standard (similar to Scout badges, but digital). A set of skills can form a portfolio accessible via the web or dedicated app. As we transition to a model of lifelong learning, we can foresee people earning these badges throughout their life, and perhaps professional or job-hunting networks (like LinkedIn or Monster.com) may one day have a function to search by badge to find the best candidates.

Technical Analysis

Infrastructure

Education 3.0 is primarily digital - since everything boils down to zero’s and one’s, automation and computation can be applied to create efficient, verifiable workflows.

Software Stack

At present all of the software stack we have used in XLP has been traditional server-based microservices. Decentralized Apps (DApps) are still some way off when it comes to capabilities.

- Digital media creation tools like MediaWiki, WordPress, Jupyter Notebook, etc

- Tools to extract, analyse and write that data to blockchain: Logstash, Elastic Search, TensorFlow

- Tools to visualize that data for human assessment (if required): Kibana

- A front-end to tie all of this together

Smart Contracts in Depth

We use smart contracts throughout the whole process outlined above:

- Educators putting their courses on the course marketplace

- Students electing to take courses

- Educators assigning grades to students

In addition, we use digital signatures to prove ownership and work on certain assets:

- Courses created by educators

- Coursework done by students

- Qualifications, signed by both student and educator

Signing a Smart Contract

The first contract signed by students is the constitution, which outlines their rights and responsibilities. To do this they need to set up a digital identity, typically a public/private key pair using the PGP standard:

OpenPGP is the most widely used encryption standard in the world. It is based on PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) as originally developed by Phil Zimmermann. The OpenPGP protocol defines standard formats for encrypted messages, signatures, and certificates for exchanging public keys. PGP & GPG is an easy-to read, informal tutorial for implementing electronic privacy on the cheap using the standard tools of the email privacy field - commercial PGP and non-commercial GnuPG (GPG)[26]

PGP uses two keys for encryption - a private key to encrypt messages, and a public key to decrypt them. Bruce Schneier writes[27]:

“Putting mail in the mailbox is analogous to encrypting with the public key; anyone can do it. Just open the slot and drop it in. Getting mail out of a mailbox is analogous to decrypting with the private key. Generally it’s hard; you need welding torches. However, if you have the secret (the physical key to the mailbox), it’s easy to get mail out of a mailbox.”

A file encrypted with PGP typically looks like this:

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE----- Version: GnuPG v1.4.0 (FreeBSD) hQIOA9o0ykGmcZmnEAf9Ed8ari4zo+6MZPLRMQ022AqbeNxuNsPKwvAeNGlDfDu7 iKYvFh3TtmBfeTK0RrvtU+nsaOlbOi4PrLLHLYSBZMPau0BIKKGPcG9162mqun4T 6R/qgwN7rzO6hqLqS+2knwA/U7KbjRJdwSMlyhU+wrmQI7RZFGutL7SOD2vQToUy sT3fuZX+qnhTdz3zA9DktIyjoz7q9N/MlicJa1SVhn42LR+DL2A7ruJXnNN2hi7g XbTFx9GaNMaDP1kbiXhm+rVByMHf4LTmteS4bavhGCbvY/dc4QKssinbgTvxzTlt 7CsdclLwvG8N+kOZXl/EHRXEC8B7R5l0p4x9mCI7zgf/Y3yPI85ZLCq79sN4/BCZ +Ycuz8YX14iLQD/hV2lGLwdkNzc3vQIvuBkwv6yq1zeKTVdgF/Yak6JqBnfVmH9q 8glbNZh3cpbuWk1xI4F/WDNqo8x0n0hsfiHtToICa2UvskqJWxDFhwTbb0UDiPbJ PJ2fgeOWFodASLVLolraaC6H2eR+k0lrbhYAIPsxMhGbYa13xZ0QVTOZ/KbVHBsP h27GXlq6SMwV6I4P69zVcFGueWQ7/dTfI3P+GvGm5zduivlmA8cM3Scbb/zW3ZIO 4eSdyxL9NaE03iBR0Fv9K8sKDttYDoZTsy6GQreFZPlcjfACn72s1Q6/QJmg8x1J SdJRAaPtzpBPCE85pK1a3qTgGuqAfDOHSYY2SgOEO7Er3w0XxGgWqtpZSDLEHDY+ 9MMJ0UEAhaOjqrBLiyP0cKmbqZHxJz1JbE1AcHw6A8F05cwW ===zr4l -----END PGP MESSAGE-----

In the context of email:

- Alice and Bob agree on a public key algorithm.

- Bob sends Alice his public key.

- Alice encrypts her message with Bob’s public key and sends it to Bob.

- Bob decrypts Alice’s message with his private key.

Writing a Smart Contract

Smart Contracts are often written in the Solidity programming language, although LLL and Serpent are also available. They are then run on the Ethereum Virtual Machine, which implements a full stack Turing-complete computer on the blockchain.

XLP Philosophy

Micro, Meso, Macro

The XLP curriculum has three tiers:

Macroscopic in Nature

Globally search and compile relevant information, and creatively tell a compelling story using trustworthy data sources and presentation techniques.

Mesoscopic in Sorting Order

Apply optimization technologies and understand the principles of optimal limits, so that participants and teams can apply optimization to all their learning activities.

Microscopic in Contexts

Guide participants to be acquainted with domain-specific vocabulary and rules, so that they can leverage existing bodies of knowledge in an organized manner.

The three categories of courses are built on top of our Remix platform, which provides a foundation of industry-standard tools to help XLP participants achieve the goals of their curriculum.

The MD's and ME's learn individually and collectively. The community of sponsors, MD's, and ME's is a microcosm of a larger context – for example, a university, a society, or a nation. XLP challenges every learning team to be a focused, goal-oriented microscopic society in a digital publishing/learning workflow environment.

Theory U

Theory U is a change management method created by Otto Scharmer, who has worked with Tsinghua University and Xu Lili (Theory U's China Coordinator) to refine XLP. The principles of Theory U are suggested to help political leaders, civil servants, and managers break through past unproductive patterns of behavior that prevent them from empathizing with their clients' perspectives and often lock them into ineffective patterns of decision making.

Several of XLP's steps correlate with Theory U:

By following these principles, we can achieve several beneficial outcomes:

Early Success

Provides resources and knowledge that enables participants to kick off their learning journey with excitement.

Fail Early, Fail Safe

Ensures participant learning assignments are challenging enough, so they can observe their shortcomings and correct their course of actions in the early stage of the mission.

Convergence

Guide participants to re-combine their team structures to create a synergistic product/service with other teams.

Demonstration

Every learning program should end with a ceremonial event that allows participants to summarize their learning experience and present it to other people who may be future XLP participants.

Lessig's Four Forces

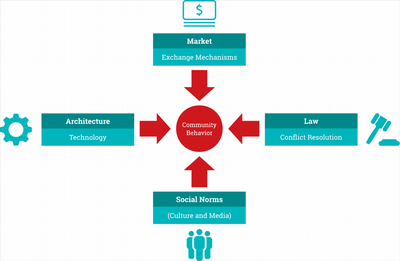

Lawrence Lessig's Code Version 2.0 states that a number of forces regulate the behavior of individuals in a society or community:

Law: The Rules a Community Recognizes

- Imposes constraints on the behavior of members by explicitly threatening punishment or sanctions that the community as an entity will enforce.

Social Norms: How a Community Expects You to Behave

- Similar to the law in that norms constrain behavior of community members

- Unlike the law, community members impose social norms on each other informally

- Whereas the law, and (prospective) punishment for breaking the law, is explicit, social norms are understood by all, or most, of the community without being explicitly stated or mandated.

Market: How Much Do You Pay?

- Enables buyers and sellers of goods, services, information, labor, and capital to exchange.

- The market forces of supply and demand determine the equilibrium level of prices in each respect market.

- Implicitly regulates behaviour of community members, for prices can fluctuate rapidly dependent on consistency and reputation.

Architecture: The Way the World Is

"The way the world is, or the ways specific aspects of it are."

- The way a product (not a service) has been designed, created, manufactured, or built.

- Regulates community members by imposing physical or technical/technological constraints.

- Special due to "agency" - does not require direct human intervention to operate (whereas other forces require police force, community members, merchants, etc), so it is "self-executing."

While each of these regulating forces is separate and distinct, all four influence each other as they regulate the behavior of community members.

Example: Smoking

In Code version 2.0, Lessig uses the regulation of smoking to illustrate the operation and interdependence of these four forces. If you want to smoke, Lessig asks, what constraints do you face?

Law

Federal, state, and local laws laws regulate:

- Minimum age and ID requirements

- Where you are permitted to smoke

- Tax on the purchase of cigarettes (aiming to reduce smoking incidence)

Social Norms

Social norms can constrain behavior even more than laws:

- Smoking in the house of a non-smoking friend

- Smoking near children in restaurants

Market

- The higher the price of cigarettes, the more financially constrained you are by smoking

- Higher insurance premiums for smokers reduces the desire to smoke

Architecture

The way cigarettes are designed and manufactured.:

- Filterless cigarettes are more dangerous, so more pressure to reduce smoking. Ultralights may tempt you to smoke more (thus costing more in terms of money and social norms)

How do the Four Forces Interact?

The four forces are interdependent; they interact, and influence each other as they regulate the behavior of individuals in the community. A change in one may influence another. Using the example of smoking:

Social norms → Market

Market → Law/Social norms

How do the Four Forces Relate to XLP?

Since XLP is a methodology for crowd-learning, these four forces also (by definition) regulate the behavior of individuals in each micro-learning community, and ultimately increasingly large macro learning communities.

Law

The law is constituted by XLP's digital recording infrastructure (legal evidence collection mechanism), which allows the filing of complaints, patent filing, and law enforcement.

Social Norms

One of the most important forces shaping social norms in XLP is the idea that all learning outcomes must be demonstrable. One of the most important end products is publishing the crowd-learning results online using a digital publishing system.

Market

XLP's transaction validation system records and validates transactions executed in the crowd-learning environment.

Architecture

XLP's technology architecture is one of the most important forces that regulate the behavior of individuals in our crowd-learning environment. Architecture is the only one of the four forces that, once created or enabled, does not require direct human intervention to operate. It functions alone and directly; that is, it is "self-executing."

The architecture in XLP's crowd-learning environment is the Remix Platform, a combination of hardware and software. A later section in this manual will describe it in detail.

The Four Forces, XLP, and The Real World

A noteworthy feature of XLP is how each force within a specific micro- or macro-learning community interacts with the same force in the "real world." For example, much of XLP's legal framework interacts with that of the real world: It is difficult to divorce the two, given that the real world's legal frameworks and mechanisms have evolved over centuries, and to regulate the individuals in a community. Patents filed in the XLP crowd-learning environment may very well also be filed in the real world, for example. If XLP is internationally and legally recognised, then this process of duplication may become automatic.

Similarly, given that one of the most important end products of an XLP activity is publishing the crowd-learning results, it is natural that these results are published via a real-world means like social media, other online media, or traditional media that is accepted by social norms.

In the market, a product or service might attract investment in the XLP environment – and might attract real-world investment too. Intellectual property in XLP's environment might also be bought and sold in the real world.

Finally, XLP's architecture has its roots in the public commons of universities, and specifically physical campuses and other resources that enable the crowd-learning environment to emulate the the real world to a large degree. This is an important factor in XLP enabling learning on a large and public scale.

Technical Analysis

Containerization

Containers are the foundation of XLP, the Remix platform, and XLP's Digital Publishing Workflow:

- XLP creates replicable, containerized learning missions, which can then be deployed and scaled up anywhere in the world

- Remix provides the infrastructure to perform this digitally - i.e. Docker and Kubernetes

- participants create containerized digital assets using XLP's Digital Publishing Workflow, as a record and proof of the work they have performed in the mission.

Docker Containers

Docker is an operating system abstraction layer, providing an abstraction boundary which manages collective boundaries and experience for its users. A Docker container 'contains':

- An operating system (often Linux/Windows/MacOS)

- The programs you want to run on the operating system (for example, WordPress/Mediawiki)

- The application and configuration data for the program (for example, WordPress media assets, WordPress configuration details)

- The data for the program (if WordPress, a database of MySql/Mariadb)

This container and its data(volume) can be save/exported from the Docker filesystem and be loaded, for easy deployment anywhere.

Like an operating system, Docker:

- Authenticates the container via its hash

- Schedules priorities, for example what resources the container has access to

- Manages input and output, for example how many of the host machine's resources it may use.

What do We Run in Docker?

Namespaces

Computers operate on levels of abstraction. Otherwise we would be dealing directly with ones and zero's. A common kind of abstraction is a namespace, which organizes and names objects. Some examples include:

- Memory registers: Each register has it's own unique address

- Filenames: Each file on a system has it's own unique path and filename combination

- URLs: Each website is reached via different URL

Containers also have their own unique namespace, namely their 256-bit hash. An example hash (shown in hexadecimal format) would be:

7f83b1657ff1fc53b92dc18148a1d65dfc2d4b1fa3d677284addd200126d9069

This hash acts as a digital fingerprint, and is highly secure since there are 25632 combinations which would take 3x1051 years to crack if using fifty supercomputers.

Verification and Security

With filenames or URLs, you have no guarantee you'll actually get what you think you'll get. Today *google.com* might take you to a search engine. Tomorrow Google may get hacked and you could end up on a site that *looks* like Google but steals your login credentials.